Reba Harris’ Memoir: ‘Living Life After the Fires of My Sorrow’

Reba Harris grew up with nothing. As a Black woman in north-central Indiana living through the nation’s struggles with race, society did everything it could to ensure she would be forgotten.

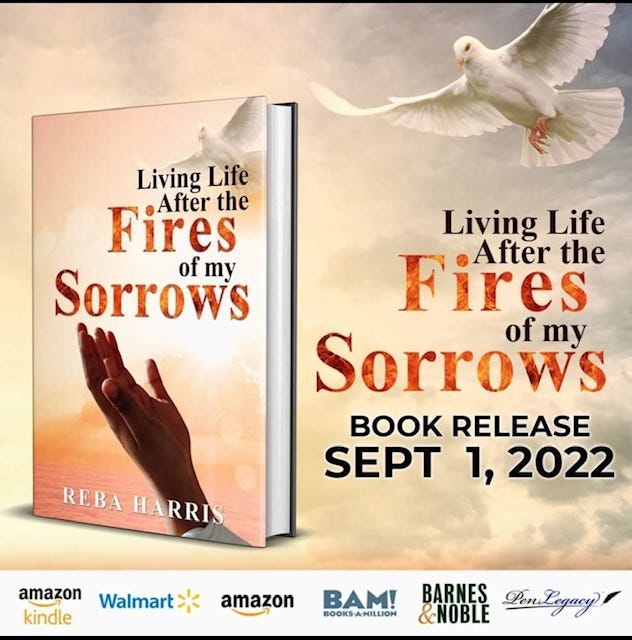

Now, Harris is an author; with one book set for release Sept. 1 and another already in the works. The founder of the Gilead House, a highly regarded drug and alcohol treatment center in Kokomo, the revered, 81-year-old, life-changing savior and spiritual sister spent 22 years building her ministry. She has penned a book about her life and mission entitled, ‘Living Life After the Fires of My Sorrow.’ It is a riveting and revealing read.

The book tells Harris’ story and explores her incredible, albeit improbable, life journey.

“To start with I was born poor, and didn't get to go to school, because I was Black,” she said. “I'm from Marion, Ind., and so we didn't get to go school with the white kids to learn like that. We weren't allowed to go to the park. We weren't allowed to go roller skating, and we were not allowed to swim in the pool, none of that. And so we went to a one-room school. We had eight classes and one teacher. We didn’t get much education. So, I am uneducated as far as that goes, they think.”

Harris’ early years belied the fact she possessed “the intellect or pedigree to go out and start something.” She had a chorus of naysayers her book recounts.

“I’m a factory worker,” said Harris. “Factory workers don’t know anything. What’s a factory worker trying to do saying God took them to the mountaintop and told them to do something?”

Well, Harris, an Indiana Wesleyan University graduate, did do something; she’s been saving and repairing lives at Gilead House. And her book tells her story. Like her years of service, writing the book was something she was led to do.

“I did it because people said God has done a lot of miracles for you, and he has,” Harris passionately admitted. “I know for a fact that there's people, men and women, sitting around with something in them that they would like to do, but they figure they're not smart enough, rich enough, savvy enough and so they don't do it. And I know that.

“And so when I thought about that because I, too, am not someone that you would think of as writing a book, I got to thinking about how God has done so many miracles here; just so many miracles for us to be open and to be open for 22 years, with no more than we have. And I said, I want someone to know that if God has given them an assignment, I want them to know that God will see them through it.

“My whole mindset was it was not going to be this hard. I thought, because this is something God wanted, that people would rally around and say, yes, let's do this, and we would ride off into the sunset.”

Not so.

Harris says she has begrudgingly learned after years of painful, hard work that “just because God wants something doesn’t mean man does.” She contended during our wide-ranging interview that she doesn’t “fit the picture” of an author or trailblazing recovery advocate and activist. She put aside her retirement years to tackle a goal.

“We expect me to be white. You expect me to be thin and to be more pizzazzed and an intellectual, to do something of this nature,” she opined. “That's what we would expect, and that's not who we got at all. I know for a fact that when I first started going around asking, and I know it's not easy, I would think it's very difficult to follow someone who says I have a vision.

“I mean that has to be hard, because yeah, you and who else? But I still think that we kind of have in our mind the intellectual to do something of this nature; to start a ministry. What would be in your mind and your idea of someone who would say, ‘God asked me to start a ministry?’ What would you think?”

She said Kokomo did not know her two decades ago, and the city already had two treatment centers, “and people were not dying. They were destroying their families, but they weren’t dying.” One of her residents recently told her, “My momma used to pass out everyday on the couch from her prescription pills, and I had to raise myself.”

“Now we have the results of years ago, but we didn’t have the vision years ago to see the people” said Miss Reba, as she is affectionately called. “When I first started, I was seeing women who were addicts. Now, I’m seeing the children of the addicts. I know their parents. A great deal of our women have addict parents. It may be covered up because they’re professional, but they are addicted to something.

“We have women here whose mothers are on heroin, and alcohol is very big still. We didn’t do anything about it 22 years ago because we didn’t see it as a problem, and now we have the results of neglecting the addict. now we’ve got their children.”

Harris credited Laura O’Donnell, an attorney, benefactor, and daughter of her longtime donors for helping to keep Gilead House afloat. In fact, she recently raised $30,000 dollars during a fancy fundraiser at The Experience.

“My dad and Miss Reba have known each other for years,” said O’Donnell. “When I flew back to Kokomo after being gone for awhile, I started getting involved. As a criminal defense attorney, I know firsthand the importance of what Miss Reba is doing. I send my clients there on a regular basis. That is their opportunity. I’ve been given every opportunity in life, and I need to give that back.

“A 30-year-old could not keep up with Miss Reba, but I think, she is a testament to God’s plan. She does what she feels she is led to do, and she does an amazing job at it. She is the epitome of someone who has absolutely dedicated her life to helping others.”

“Living Life After the Fires of My Sorrows” is slated to be published by Pen Legacy on Sept. 1 in paperback and Kindle formats. Pricing and availability will be detailed at a later date.